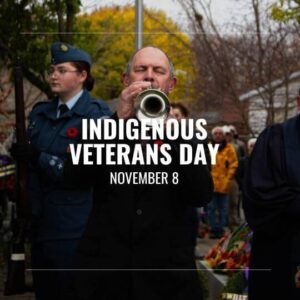

November 8 marks Indigenous Veterans Day, a day established in 1994 to commemorate the contributions Indigenous people have made to different branches of Canada’s military. In Canada, the term Indigenous encompasses First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. More than 12,000 Indigenous people have served since 1914, including over 4,000 people during the First World War and more than 3,000 throughout the Second World War. These individuals have distinguished themselves as skilled snipers, reconnaissance scouts, and “code-talkers.” The latter role consists of using Indigenous languages to secure military communications from interception by the enemy. Indigenous service continues today, with current members of the Canadian Armed Forces supporting peacekeeping missions abroad and assisting with domestic crises here at home, such as natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic.

November 8 marks Indigenous Veterans Day, a day established in 1994 to commemorate the contributions Indigenous people have made to different branches of Canada’s military. In Canada, the term Indigenous encompasses First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. More than 12,000 Indigenous people have served since 1914, including over 4,000 people during the First World War and more than 3,000 throughout the Second World War. These individuals have distinguished themselves as skilled snipers, reconnaissance scouts, and “code-talkers.” The latter role consists of using Indigenous languages to secure military communications from interception by the enemy. Indigenous service continues today, with current members of the Canadian Armed Forces supporting peacekeeping missions abroad and assisting with domestic crises here at home, such as natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic.

First Nations have a proud history within Canada’s military, a tradition rooted in longstanding alliances and commitments, some of which trace back to before Confederation in 1867. As noted by the Assembly of First Nations’ Veterans’ Council, “First Nations have a long history of volunteering to enlist to serve the country and their homelands” (Veterans Council, n.d.). The Kenhtè:ke Kanyen’kehá:ka community (also historically called Tyendinaga or the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte), which neighbours Prince Edward County, has a deep connection to military alliances as represented in some of our region’s first treaties. During the American Revolution, a large number of Kanyen’kehá:ka people aligned with the British. In partial recognition of this loyalty, they were granted land in the region now known as Eastern Ontario along with United Empire Loyalists through the Crawford Purchase treaty of 1783. Unfortunately, over time this territory has been diminished significantly and recognition for their contributions has been inconsistent. However, Kenhtè:ke has steadfastly upheld its proud tradition of military service. Community members continuously volunteer to serve in Canada’s military, demonstrating loyalty and bravery in the face of the many forms of adversity.

In addition to individual service, Indigenous-focused programs within the Canadian Armed Forces such as the Canadian Rangers and Bold Eagle support Indigenous participation. Bold Eagle includes a Culture Camp led by First Nations Elders to provide traditional teachings, followed by basic training in Wainwright, Alberta (Pryce, 2015). Other programs like Raven, Black Bear and the Canadian Forces Aboriginal Entry Program (CFAEP) offer similar opportunities, allowing Indigenous participants to develop skills while maintaining important connections to their cultural heritage.

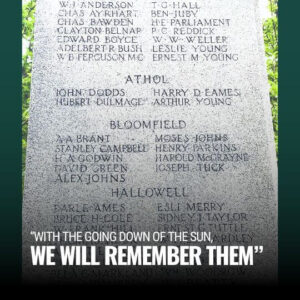

Among the Kenhtè:ke community members who served in World War I was Alfred A. Brant, Regimental #219956, who enlisted on October 5, 1915, in Picton. Born on July 14, 1879, to Peter Joe and Debby (Claus) Brant, he was injured in combat multiple times across 1916, 1917, and 1918, exemplifying bravery and resilience on the front lines. Brant miraculously returned home and passed away in 1959. He was laid to rest locally in Tyendinaga (Christ Church) First Nations Cemetery.

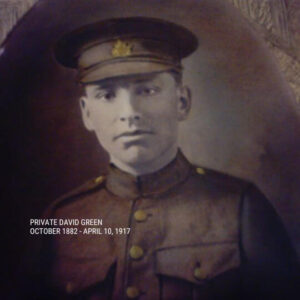

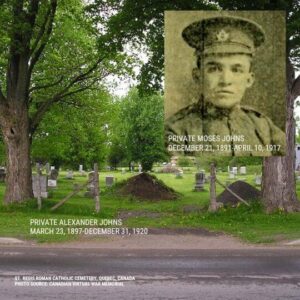

Private David Green of Kenhtè:ke and Private Moses Johns of Akwesasne, both fell in action on April 10, 1917, at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in France. Green, buried in Lapugnoy Military Cemetery, France, was 34, while Johns, buried in Canadian Cemetery No. 2 in France’s Canadian National Vimy Memorial Park, was 26. Johns’ younger brother, Private Alexander Johns, followed him by enlisting to serve in the First World War as well. He tragically passed away in 1920 two years after hostilities ended from tuberculosis, a condition attributed to the conditions he endured during his military service.

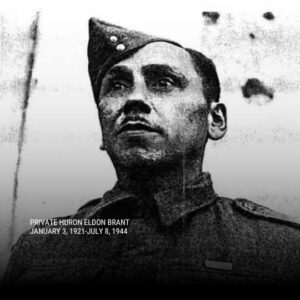

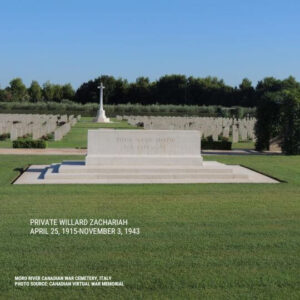

Private Huron Eldon Brant of Kenhtè:ke served with bravery in World War II, receiving the Military Medal for his actions in Sicily in 1943. He courageously defended his fellow soldiers in a Bren gun attack on an enemy force, inflicting severe casualties. He was killed a year later and is remembered at the Cesena War Cemetery in Italy. Private Willard Zachariah, another Kenhtè:ke serviceperson, was wounded in combat and passed away on November 3, 1943. Originally interred in the British War Cemetery in South Severo, he now rests at the Moro River Canadian War Cemetery in Italy.

As settlers on this land, we at Base31 acknowledge the service and sacrifices of Indigenous veterans past and present with gratitude and respect. We honour the contributions of Indigenous communities and express sincere thanks to Kenhtè:ke community members – particularly researchers Trish Rae and Steven Lindsay-Maracle – as well as the Assembly of First Nations for preserving and sharing these stories to ensure that the bravery of Indigenous veterans is recognized and remembered today and into the future.

A Note on Terminology: We at Base31 wish to support Indigenous self-determination. In the context of this article, that means honouring terms that local Indigenous peoples use to describe themselves and their communities today. Presently, the region historically known as Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte and/or Tyendinaga is beginning to be more commonly called Kenhtè:ke by the Indigenous peoples there, who call themselves Kanyen’kehá:ka in their language. The name “Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte” was established by colonial powers: the term “Mohawk” is derived from early Dutch settlers mishearing the name these peoples were called by the Mohican peoples, and the name “Quinte” is taken from a French misappropriation of the name of an Indigenous village on the north shore of what is now Prince Edward County. The name “Tyendinaga” is taken from a colonial Anglicised spelling of Kanyen’kehá:ka leader Joseph Brant’s traditional name, Thayendanegea (Brant was heavily involved in supporting the British during the American Revolution). Taking these distinctions into consideration, we have used the term Kenhtè:ke in lieu of Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte and Tyendinaga, and Kanyen’kehá:ka instead of Mohawk in this article.

References:

Canada, V. A. (2021, November 8). Ministers of Veterans Affairs, Indigenous Services, National Defence, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northe. . . https://www.canada.ca/en/veterans-affairs-canada/news/2021/11/ministers-of-veterans-affairs-indigenous-services-national-defence-crown-indigenous-relations-and-northern-affairs-mark-indigenous-veterans-day.html

Canada, V. A. (2017, November 27). Indigenous Veterans – Veterans Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/classroom/fact-sheets/aboriginal-veterans

Crown Grant to the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte. (n.d.). The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/crown-grant-to-the-mohawks-of-the-bay-of-quinte

Pryce, P. (2015, June 25). Engaging Aboriginal Youth in the Canadian Armed Forces. NAOC. https://natoassociation.ca/engaging-aboriginal-youth-in-the-canadian-armed-forces/

Remembrance: Indigenous military | Canadian War Museum. (2024, August 19). Canadian War Museum. https://www.warmuseum.ca/remembrance-day-resources/indigenous-peoples-and-canadas-military

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN). (2024, July 22). Veteran’s Council – Assembly of First Nations. Assembly of First Nations. https://afn.ca/about-us/councils/veterans-council/